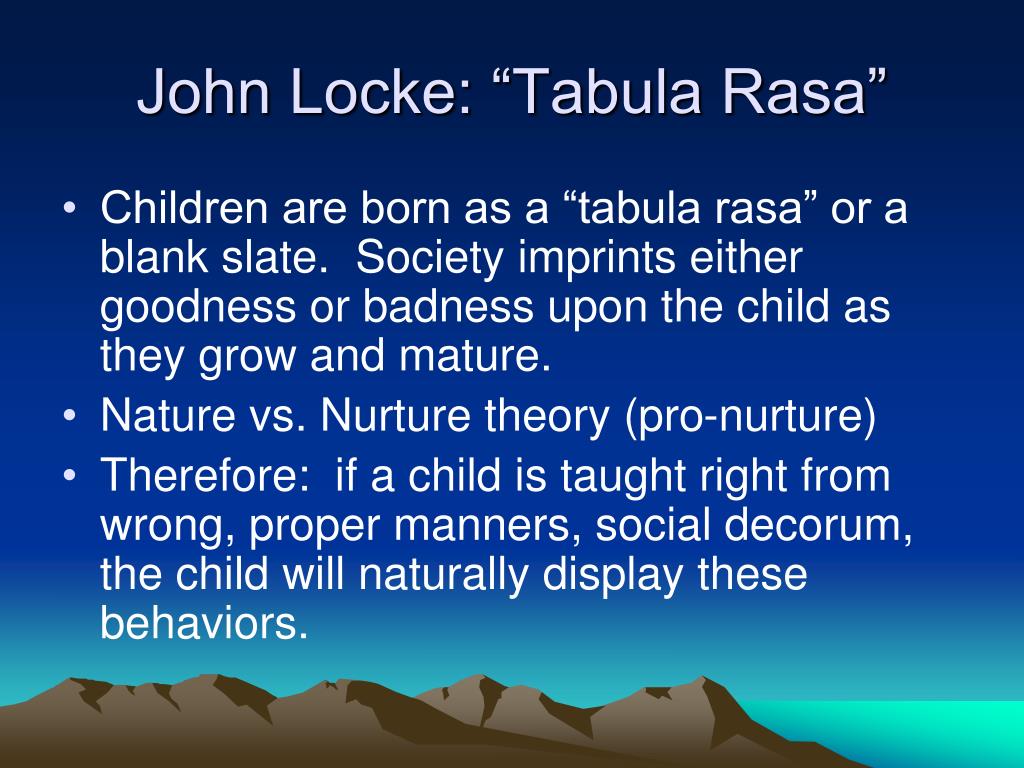

Our neurochemistry is our lowest common denominator, and this brings a nuanced counterargument to Locke with an appeal to the universality of emotions: because emotions are neurochemically mediated, they are present across cultures as part of our genetic inheritance. What Locke could not appreciate, however, was that the same neurochemistry that allows significant flexibility and makes human beings malleable to their environment also predisposes them in certain basic ways. Modern neurological studies have bolstered Locke’s position, proving the plasticity of the brain and hence its susceptibility to influence. Since the means to make such a distinction were missing, the defender of innate ideas will have to demonstrate that certain ideas could not have been acquired by reason. More generally, Locke intended to prove that there was no principled way to distinguish between innate ideas and those acquired through the process of reasoning (induction or deduction). Moral notions, in particular-which in contemporary times have been demonstrated to vary significantly from one culture to another-stand as evidence against the innateness of ideas. Though he mostly confines his discussion to “children and idiots,” similar themes have been expressed by those who advocate concepts and paradigms of cultural relativity.

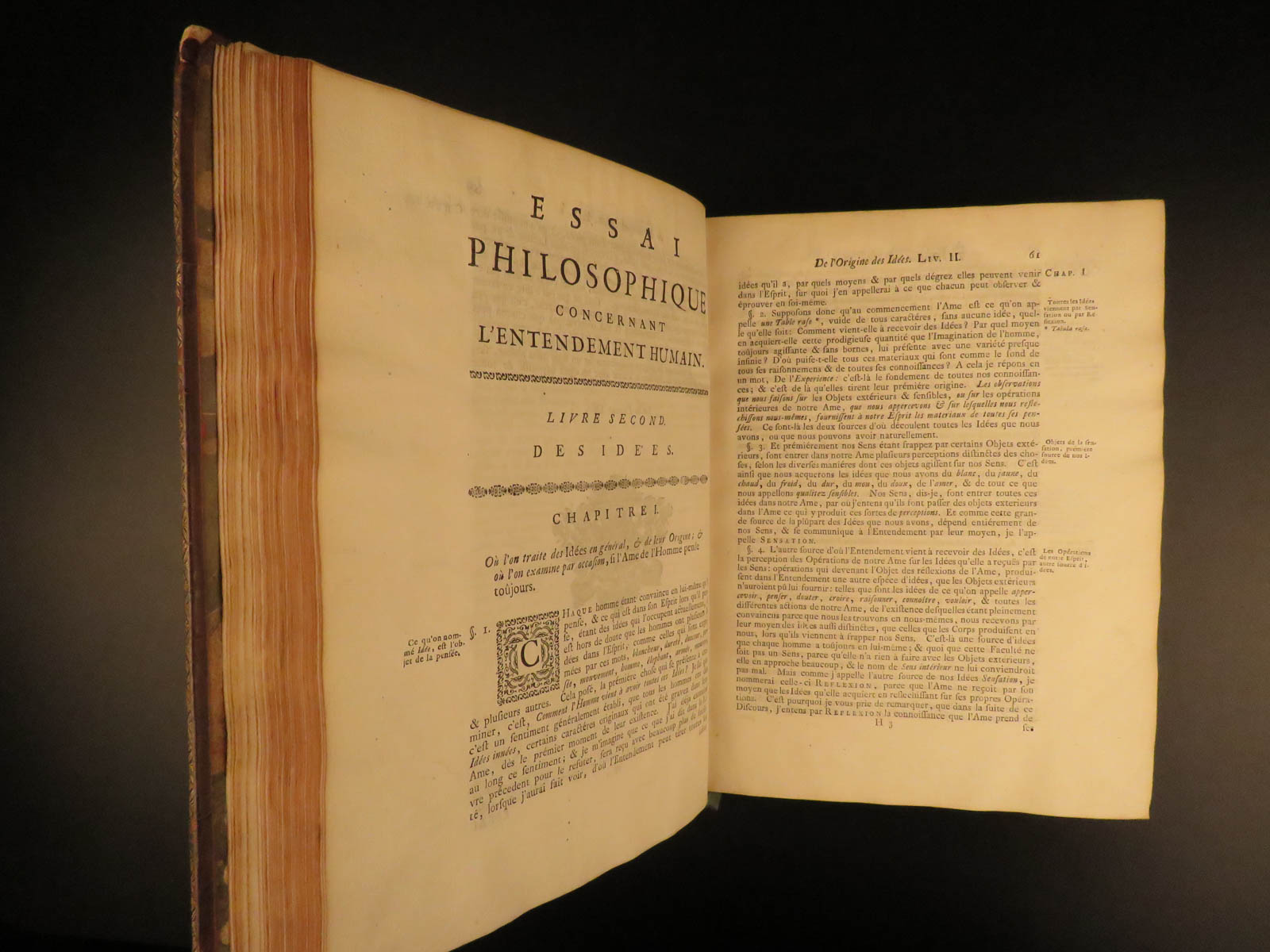

If such ideas were innate, there should be no obstacle to all human beings recognizing their truth immediately. While Locke was right to eschew particular innate ideas, his lack of familiarity with evolutionary theory and neurosciences prevented him from grasping aspects of human nature that are inherited and universal and grounded in our shared neurochemistry.įamously, Locke discredited innate ideas by arguing that logical and mathematical truths, which make the best candidates for innate ideas, are by no means universally accepted. This debate, however, missed some crucial insights. The Lockean challenge to innate ideas represented a healthy exercise of philosophical parsimony and an important step forward but, at the same time, it led to another dichotomy between innate and acquired aspects of human nature more generally. Instead, he advocated a tabula rasa, or blank slate, image of the mind. The notion of innate ideas was subsequently popularized in Western philosophy and reemerged with thinkers as influential as Descartes.Īt the other side of the spectrum, John Locke came to be known as the most ardent critic of these concepts, believing that there was no evidence for innate ideas whatsoever. The notion of anamnesis, or recollection, is foregrounded in several of the Dialogues, and serves as a kind of digression in a number of others. Contemporary neuroscientific research and an understanding of the predispositions of our neurochemistry challenge classical thought on human nature and inform us of fundamental elements that must accompany good governance.Īre we intrinsically good or bad? Are we born with innate morality or with a blank slate? The question of the original endowments of human beings has intrigued philosophers since at least Plato’s day. Nevertheless, there are further invaluable insights from neuroscience that have remained less explored. These recent initiatives serve as reminders that sound public policies must evolve in strong connection with an understanding of human psychology, emotions and the sources of happiness and satisfaction. The World Happiness Report, a recent initiative, attempts to analyze and rate happiness as an indicator to track social progress.

It was also hoped that discussions about happiness would serve to refine the wider debate about the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2015-2030 and the standards for measuring and understanding well-being.

The discussion was bolstered when the UN passed a critical resolution in July 2011 inviting member countries to measure the happiness of their people as a tool to help guide public policies. More recently, the study of happiness furthered the debate in public policy, as many governments brought up the necessity for new measures of social progress. Economists, social theorists and philosophers have long analyzed the incentives of human actions, decision making, rationality, motivation, and other cognitive processes.

Studies of human behavior and psychology have received extensive attention in public policy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)